Tea Bowl and Tea Cup

Perspective, Context, and Relativity

I ‘look’ with the intent of perceiving the artistic elements of what I am viewing rather than the intellectual dissection of information. To that end, I want to be moved and inspired, and respond to the potential of experiences I encounter.

I approach the process of making as a creative process giving myself the freedom to improvise, or run with an idea and see where it takes me, to keep the work alive and evolving. If I do not approach my work in this way, then the work stagnates and will precipitate the beginning of the end, which leads to a slow death.

I am interested in making my own work more fluid. This may be the result of softer clay, or more spontaneous forming techniques: less attention spent on technical perfection and more time spent on understanding the 'wholistic' approach to concept, material and process.

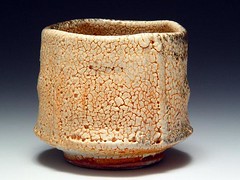

In the wood fire genre, the romanticism of the firing effects often dictates or overshadows the other aspects of the work. But actually, the material and forming process, as well as surface color and texture must be compatible. The firing alone cannot make up for weaknesses that may exist in either the clay character or forming process.

I respond to the beauty that exists in the imperfections of Nature; a sense that perfection as we know it does not necessarily equate with beauty, that in actuality, beauty exists. It is for us to behold, discover and expand our vision to appreciate a beauty that exists outside of a predetermined western perception.

A torn leaf, a twisted branch, a crack in a wall, it is all about perspective and perception.

When related directly to ceramics, I think of these terms as dimensions or layers. Even cracks in clay can be a dimension of beauty depending on how they relate to the other aspects and qualities of the piece in question.

For More Work: Jeff Shapiro and Contemporary American Ceramics

AKAR